With many residents of Woodlands County utilizing well water, the municipality hosted a virtual workshop on October 21 on managing wells. The event streamed live and enabled attendees to ask questions in real-time. Multiple specialists were on hand, including Jeff Hammer, a Public Health Inspector for Alberta Health Services.

Hammer discussed the importance of testing water and why it’s essential to do so. “We have two types of tests available at the health units. One is a bacteriological bottle which we test for total Coliform and E. coli. Total Coliform is an indicator of bacteria, and E. coli is basically fecal matter which you never want to see. The other type of test we have is a chemical water sample. It does a bunch of minerals and metals and has some more health parameters associated with it.” Hammer said that some of the minerals and metals tested for include manganese, lead, arsenic, and the pH value of the water.

He said that testing well water is vital to help establish a baseline because water quality can change over time. “If you are in an oil and gas region and they do some drilling, and your water quality changes, and you don’t have proof of that change, then you’re going to have a hard fight on your hands. You want to have a good history of what your water quality is just in case something funky happens with resource development in your area.”

Routinely checking water quality also comes down to safety. “A lot of times, taste or smell is not evidence of a good or bad water source, so the only way to tell is bacteriological testing or chemical testing if you’re worried about heavy metals or things like that.”

He said that between 2017-2020, out of 23,921 wells that were sampled, 21 percent had total coliform exceedances, and nine percent had fecal coliform present (E. coli). On the chemical side, 9,109 wells were tested, resulting in up to 21 percent having exceedance of either a chemical, trace metal, or health-based chemical, which can include nitrate/nitrite or arsenic. He explained that 19 percent of the province-wide testing had an over-exceedance of manganese, affecting area wells.

He said that running the tap for five minutes before taking a sample is important when testing the water. As for who should test their water, Hammer noted that a new well, or a new to you well, are critical times to test as it sets a baseline. He said that having a change in taste or odour or colour is another. “If you have drought, you have less water going through, so sometimes your metals will concentrate, which might have a health effect. If you have flooding in the area, then water can go over your casing or percolate down through the well casing edges if you don’t have a good seal and contaminate your well.”

He said that in that case, residents would want to test for bacteria. “Periods of prolonged non-use, where you have stagnant water sitting in your well for a long period of time, you’ll want to flush that out and then test for bacteria. You will have biofilm growing, and that is a good house for bacteria to live in.” He said that bringing a new baby home is another prime time to test the water. “Lead and magnesium can affect brain development, and fluoride can cause dental fluorosis. There are a fair bit of reasons to test with a newborn.”

Families that experience chronic diarrhea or illness should also test. “If you do any major plumbing work, you should shock chlorinate and then test. Once you pull out our pump, you put that on the ground or a clean tarp, you’re going to get those coliforms on the material, and when you stick it back in the well, you’re going to contaminate it with the coliforms and potentially other bacteria. So, do a shock and then test afterwards.”

As far as the frequency that homeowners should sample their well water, Hammer said it depends on the type of well. Treated surface water sources and shallow (GUDI) wells that are 50 feet or less or directly influenced by surface water should be tested for bacteria four times a year. Deeper wells that reach high-quality groundwater sources should be tested twice a year. Chemical testing for trace metals should happen every three years, regardless of the depth.

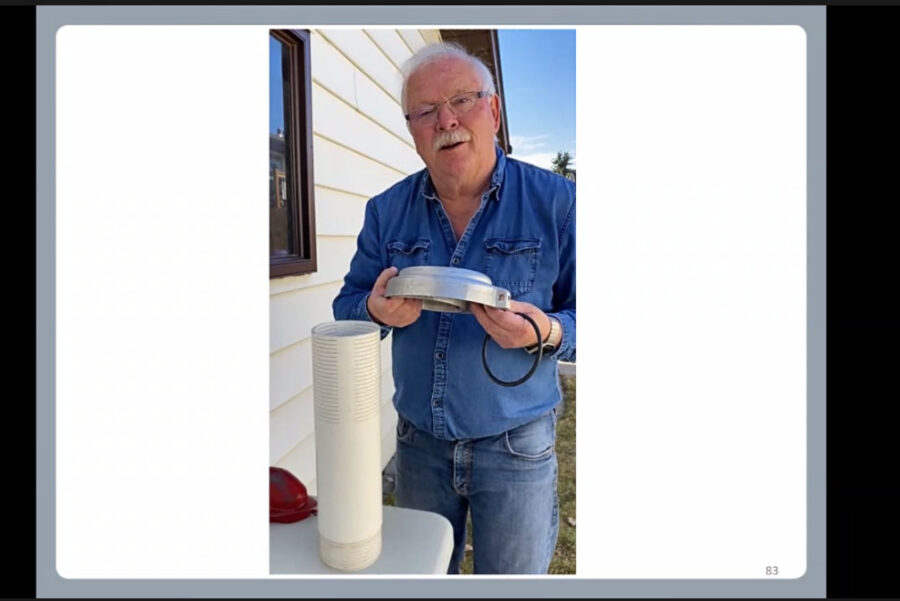

When it comes to collecting samples for testing, Hammer said that residents need to use approved containers specific to testing, which can be picked up at health units. “If you bring water to the health unit in a pickle jar or something else, it will be rejected, and we won’t process it because it will be contaminated.”

He recommends that samples be taken from a bathroom tap. “Nowadays, the kitchen taps with the pull-out wands and the giant nozzle, I am personally finding that those sites are more prone to cross-contamination. You want cold water, and you want to run it for five minutes. If there’s an aerator on it, take it off. That’s just the little screen that you can unscrew.”

Hammer explained that water sampling at Public Health Centres is only for human consumption and not for other reasons such as agriculture. He recommends calling ahead before dropping off a sample as they only accept them on certain days and times. Learn more at www.workingwell.alberta.ca.

More Stories

Is your fire pit permit older than 2025? Then you need to get a new one

Kenyan delegation may visit Woodlands County this June

Let your voice be heard – Budget Open House happening early next month